Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Pyenv

- Pyenv Project Configuration

- Pipenv

- PYTHONPATH

- Environments and Externalisation

- Flask and Flask-RESTPlus

- The Server

- Models

- Resources

- Application Entry Point

- Unit Tests

Introduction

I have been considering Python as a language for API development. The Python ecosystem is very mature when it comes to machine learning and statistics libraries. On some projects, it may be useful to write parts of the backend in Python, so we can use libraries like NumPy, Pandas, and SciPy.

This article will describe how to get started with the python ecosystem, so we can write APIs. We’ll leave out application specific aspects like authentication and database access and will focus on the basics. As an example, we’ll build a simple REST-ful API. You can find the full code here.

The following has been tested on Ubuntu and OS X.

Pyenv

Most modern programming languages have tools that allow us to quickly install and switch between runtime versions. Similar to Node’s NVM and Java’s SDKMan, Python has Pyenv.

If you don’t already have it, you can follow the

Official installation instructions.

On OS X, you can brew it:

1

brew install pyenv

Once you have pyenv, you can install and configure any python version:

1

2

3

4

# Install the desired python version - e.g. 3.4.3

pyenv install 3.4.3

# Set it up as a global version - pyenv will reconfigure your PATH accordingly

pyenv global 3.4.3

Pyenv Project Configuration

After installing Pyenv, let’s create a folder for our sample API:

1

mkdir sample-python-api && cd sample-python-api

Whenever you enter a folder, Pyenv looks for a special file called .python-version.

It specifies the Python version for the project. If it exists,

Pyenv will automatically switch to the respective version.

Let’s create the file:

1

2

# Define project specific Python versions

echo "3.6.0" > .python-version

Now we can check that Pyenv detects the file and install the specified Python version.

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Should print the version from ".python-version".

pyenv local

# Installs the version from ".python-version" if not installed

# Can take some time.

pyenv install

Pipenv

PIP is Python’s most popular package manager.

Pipenv is a new package and

environment manager which uses PIP under the hood. It provides more

advanced features like version locking and dependency isolation between projects.

After installing pyenv, you should be able to add pipenv like this:

1

pip install --user pipenv

If that doesn’t work for you check the Pipenv’s installation documentation for alternative installation instructions for your platform.

Now we can install a dependency/library for our sample API:

1

pipenv install flask

This will create the Pipfile and Pipfile.lock files in the project directory.

The first one defines the dependencies and the second specifies

their exact installed versions.

Whenever we add more dependencies, they’ll be added to these two files.

Pipenv has the concept of a shell/environment which encapsulates the python process.

We can start a pipenv shell via:

1

2

3

# Initialises environment variables

# and loads dependencies

pipenv shell

This will initialise common environment variables in the current shell.

As a result, when you run python the shell will start the REPL interpreter

with all pipenv libraries loaded at your disposal:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# Initialises common environment variables and dependencies

pipenv shell

# Start the shell

python

# We have all dependencies loaded, so we can import them

> from flask import Flask

PYTHONPATH

PYTHONPATH is a special environment variable which tells the Python

interpreter where to search for modules. Let’s create two

source folders src and tests. By now your project should look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

sample-python-api/

│

├──── .python-version

├──── Pipfile

├──── Pipfile.lock

├──── src/

└──── tests/

Now we’ll need to tell Pipenv the right PYTHONPATH so the Python interpreter

can include the files from src and tests.

Whenever Pipenv starts a shell, it looks

for a special file called .env and loads all environment

variable from there.

Let’s create a .env file with the following:

1

PYTHONPATH="src:tests"

Now restart the Pipenv shell for the change to take effect.

Environments and Externalisation

In Node JS, developers use the special environment variable NODE_ENV

to specify whether the code is running in production or development mode.

Depending on the “mode”, different configuration can be used.

To follow this pattern in Python we can set the PYTHON_ENV environment variable.

For example:

1

2

# Will run in production mode.

PYTHON_ENV=production python <my_script.py>

Now let’s create a file src/environment/instance.py, which will exemplify how to

load different configurations depending on the environment:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import os

# Load the development "mode". Use "developmen" if not specified

env = os.environ.get("PYTHON_ENV", "development")

# Configuration for each environment

# Alternatively use "python-dotenv"

all_environments = {

"development": { "port": 5000, "debug": True, "swagger-url": "/api/swagger" },

"production": { "port": 8080, "debug": False, "swagger-url": None }

}

# The config for the current environment

environment_config = all_environments[env]

Our other modules can import environment_config to access environment specific

configuration. Note that the values in the above configuration are specific to

Flask, which we will discuss next.

Flask and Flask-RESTPlus

Flask is a lightweight web server and framework.

We can create a Web API directly with flask. However, the

Flask-RESTPlus

extension makes it much easier to get started. It also automatically configures

a Swagger UI endpoint for the API.

If you have been following so far, we already installed flask by:

1

pipenv install flask

Now let’s add flask-restplus too:

1

pipenv install flask-restplus

The Server

Let’s start by creating a flask server in a file ./src/server/instance.py:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

from flask import Flask

from flask_restplus import Api, Resource, fields

from environment.instance import environment_config

class Server(object):

def __init__(self):

self.app = Flask(__name__)

self.api = Api(self.app,

version='1.0',

title='Sample Book API',

description='A simple Book API',

doc = environment_config["swagger-url"]

)

def run(self):

self.app.run(

debug = environment_config["debug"],

port = environment_config["port"]

)

server = Server()

The above code defines a wrapper class Server which aggregates the flask

and the flask-restplus server instances called app and api.

We use the environment configuration to parameterise api.

The environment_config["swagger-url"] parameter defines the URL path

of the Swagger UI for the project. If it’s None, then the server won’t start

a Swagger UI.

The start method (which also uses environment parameters) initiates the server.

The server object represents the global (ala singleton) instance of the web server.

Models

The flask-restplus library introduces 2 main abstractions: models

and resources. A model defines the structure/schema of the

payload of a request or response. This includes the list of all fields

and their types. I keep all my models in a separate folder ./src/models.

Let’s create a new model ./src/models/book.py:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

from flask_restplus import fields

from server.instance import server

book = server.api.model('Book', {

'id': fields.Integer(description='Id'),

'title': fields.String(required=True, min_length=1, max_length=200, description='Book title')

})

Resources

A resource is a class whose methods are mapped to an API/URL endpoint.

We use flask-restplus annotations to define the

URL pattern for every such class.

For every resources class, the method whose names match the HTTP

methods (e.g. get, put) will handle the matching HTTP calls.

By using the expect annotation, for every HTTP method

we can specify the expected model of the payload body.

Similarly, by using the marshal annotations, we can define

the respective response payload model.

I keep my resources in the ./src/resources folder. Let’s

create a simple resource ./src/resources/book.py:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

from flask import Flask

from flask_restplus import Api, Resource, fields

from server.instance import server

from models.book import book

app, api = server.app, server.api

# Let's just keep them in memory

books_db = [

{"id": 0, "title": "War and Peace"},

{"id": 1, "title": "Python for Dummies"},

]

# This class will handle GET and POST to /books

@api.route('/books')

class BookList(Resource):

@api.marshal_list_with(book)

def get(self):

return books_db

# Ask flask_restplus to validate the incoming payload

@api.expect(book, validate=True)

@api.marshal_with(book)

def post(self):

# Generate new Id

api.payload["id"] = books_db[-1]["id"] + 1 if len(books_db) > 0 else 0

books_db.append(api.payload)

return api.payload

The above example handles HTTP GET and POST to the /books endpoint.

Based on the expect and marshal annotations, flask-restplus will

automatically convert the JSON payloads to dictionaries and vice versa.

Now let’s implement individual book retrieval and update. In the same file we can write another resource class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

# Handles GET and PUT to /books/:id

# The path parameter will be supplied as a parameter to every method

@api.route('/books/<int:id>')

class Book(Resource):

# Utility method

def find_one(self, id):

return next((b for b in books_db if b["id"] == id), None)

@api.marshal_with(book)

def get(self, id):

match = self.find_one(id)

return match if match else ("Not found", 404)

@api.marshal_with(book)

def delete(self, id):

global books_db

match = self.find_one(id)

books_db = list(filter(lambda b: b["id"] != id, books_db))

return match

# Ask flask_restplus to validate the incoming payload

@api.expect(book, validate=True)

@api.marshal_with(book)

def put(self, id):

match = self.find_one(id)

if match != None:

match.update(api.payload)

match["id"] = id

return match

Application Entry Point

We now have all necessary components to start the API. If you have followed along, your code structure should look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

sample-python-api/

│

├── .python-version

├── Pipfile

├── Pipfile.lock

└── src

├── environment

│ └── instance.py

├── models

│ └── book.py

├── resources

│ └── book.py

└── server

└── instance.py

Let’s create an entry point in the ./src/main.py file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

from server.instance import server

import sys, os

# Need to import all resources

# so that they register with the server

from resources.book import *

if __name__ == '__main__':

server.run()

To start the server in development mode:

1

2

3

4

# If you haven't already, then start a pipenv shell

pipenv shell

PYTHON_ENV=development python src/main.py

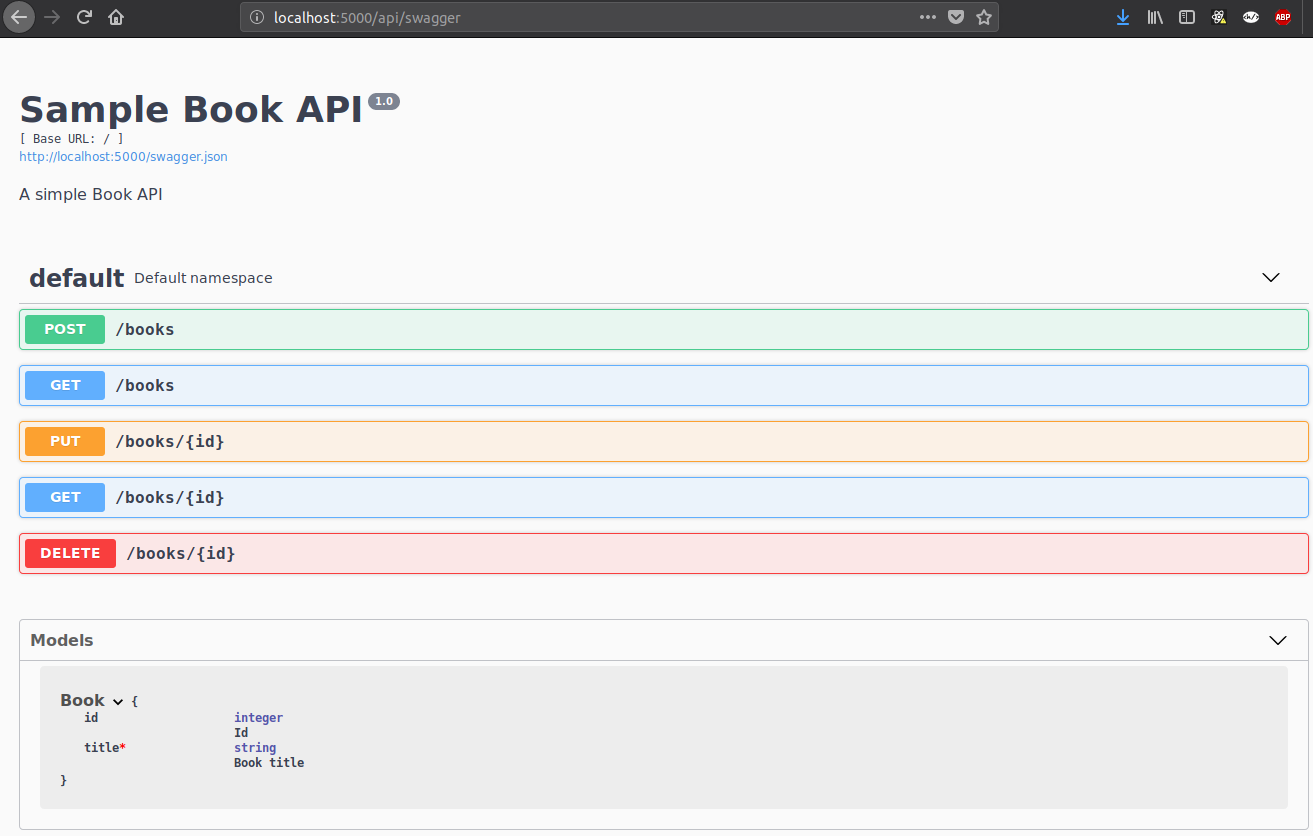

This will start the server at the default port 5000. You can access the Swagger UI on http://localhost:5000/api/swagger:

To start the server in production mode:

1

2

3

4

# If you haven't already, then start a pipenv shell

pipenv shell

PYTHON_ENV=production python src/main.py

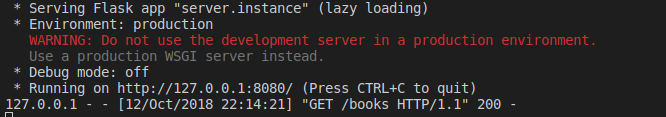

Because of our environment configuration, you won’t see the Swagger UI. You can still make API calls:

1

curl http://localhost:8080/books

Note that despite running our code in production mode/environment, we are still using flask’s embedded development server. It is not optimised for large workloads.

Refer to the official flask documentation about suitable production deployment options.

Unit Tests

We’re going to use the pytest library for unit testing. Let’s install it

1

pipenv install pytest

We’re also going to use pytest-flask, which is a pytest plug-in

for testing flask apps:

1

pipenv install pytest-flask

Pytest is quite different from other popular unit testing libraries

like junit or jest. It introduces the concept of

fixtures. In the simplest case, a fixture is just a named function,

which constructs a test object (e.g. a mock database connection).

Whenever a test function declares a formal parameter whose name

coincides with the name of the fixture, pytest will invoke

the corresponding fixture function and pass its result to the test.

When pytest starts, it looks for a special file called ./conftest.py

and runs it before all tests. This is the usual place to define

global fixtures.

Let’s define a fixture for our server in ./conftest.py:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

import pytest

from server.instance import server

# Creates a fixture whose name is "app"

# and returns our flask server instance

@pytest.fixture

def app():

app = server.app

return app

The above code defines a global fixture for our flask instance.

This is where the pytest-flask plug-in kicks in. Given the app

fixture, it implicitly and “magically” creates the client fixture,

which allows us to execute test API calls.

Let’s demonstrate this by creating a new test file ./test/resources/test_book.py.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# Import the resource/controllers we're testing

from resources.book import *

# client is a fixture, injected by the `pytest-flask` plugin

def test_get_book(client):

# Make a tes call to /books/1

response = client.get("/books/1")

# Validate the response

assert response.status_code == 200

assert response.json == {

"id": 1,

"title": "Python for Dummies"

}

Pytest expects all unit test files

and functions to start with test_ prefix. When adding more tests,

we’ll need to ensure we follow this naming convention.

To run the unit tests:

1

2

3

4

# If you haven't already, then start a pipenv shell

pipenv shell

python -m pytest

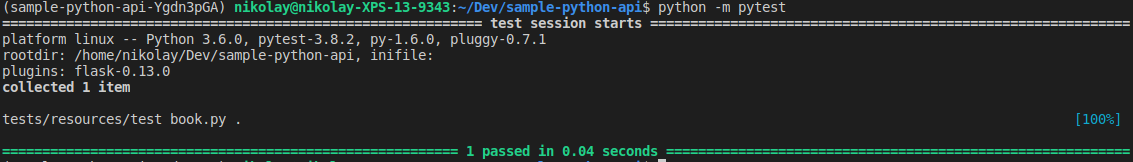

This should give us the following outcome: